Reform of Government Assets ManagementSystem & Opportunities for Foreign Merger and Acquisition

Jun 02,2003

Guo Lihong

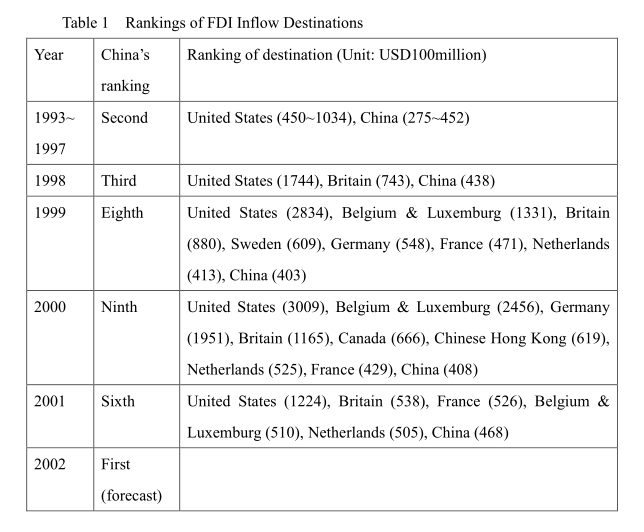

In 2002, China may overtake the United States to become the world’s largest destination of foreign direct investment. This is because, first, China’s foreign direct investment reached a new high of more than 50 billion U.S. dollars in 2002 after staying around more than 40 billion U.S. dollars annually for six years, and second, the amount of foreign investments attracted by developed countries took a nosedive in the year. Table 1 shows the rankings of the inflow destinations of foreign direct investment in recent years.

Data source: World Investment Report published annually by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

There are two forms of FDI. First, the establishment of new investment facilities and second, the merger and acquisition of existing local enterprises. The FDI among developed countries is mainly done through merger and acquisition. The latest wave of merger and acquisition started in 1995 and ended in 2000. It died down drastically in the past two years. In the United States, for example, the FDI inflow dived from 300.9 billion U.S. dollars in 2000 to only 50 billion U.S. dollars in 2002 (forecast), down by 83 percent, due to a drastic fall in merger and acquisition cases. By sharp contrast, China stood out amid the receding wave of merger and acquisition because its FDI inflow had always been mainly in the form of new business establishment and the proportion of merger and acquisition had been very small.

The striking feature of "new business establishment" was that the foreign capital investment constituted a net increase of industrial capital, which could rapidly expand production (service) capacities and could directly increase commodity (service) supplies. In a seller’s market where supply falls short of demand, this was undoubtedly the most rational mode of FDI inflow, and also a market background against which China had been able to effectively attract foreign direct investment. Merger and acquisition does not have an immediate impact on the expansion of commodity supplies. Instead, it has reflected the upgrading of enterprise quality, and its shock to the original production capacities is limited. Or in other words, its social cost is relatively low. In a buyer’s market where supply and demand is by and large in balance, merger and acquisition ought to gradually become the main mode for China to attract foreign investment in the future.

It can be expected that in the medium and immediate terms, China’s FDI inflow in the form of "new business establishment" will continue to grow. This is because China still has a market space and also because China is moving toward a "global manufacturing base". According to the exposition by Scholar Jiang Xiaojun (first issue of Management World in 2003), transnational corporations in the first half of 2002 alone issued a lot of information on their advance to China. Intel announced that another 100 million U.S. dollars would be invested in an all-round renovation of its chip packing and testing center in Shanghai and would continue to invest 500 million U.S. dollars in China. Microsoft announced that it would select a cooperation partner in China before the end of 2002 to produce Xbox. Toshiba announced that it would investment 7 billion yen in establishing a global IT production base in China. And this investment will be used for the production lines of Toshiba notebook computers in Suzhou. Sony announced that it would invest 10 billion yen in establishing a chip assembly plant in China in 2003. NEC announced that it would close down its manufacturing plants in Scotland and Malaysia and move 70 percent of its PC manufacturing to China. Leshan-Pheonix, a Motorola subsidiary, announced that it would establish a new production base in China in August 2002, with a total investment of 37.5 billion U.S. dollars. Ricoh and Matsushita announced that they would establish new subsidiaries in China. Fujitsu, Minolta and NMVisual Systems announced simultaneously that they would expand their operations in China in a big way and were considering investment in new plants. Olympus announced that it would establish a plant in China to produce digital cameras and related accessories. NEC would establish an enterprise in Shanghai to produce thin film transistor liquid crystal displays (TFT-LCD), with a total investment of 8.5 billion U.S. dollars. Nissan president indicated that his company would invest heavily in China along with a whole series of new car models. Philips indicated that it would move its display production equipment from Ciudad Juarez in Mexico to its existing production base in China before the end of 2002. Epson would close its production of scanners in Singapore before the end of 2002 and move its production lines to China. New HP’s first new product since its establishment -- Compaq Evo –were made in its plant in Shanghai, and in 2003 HP notebook computers will also be produced in China. LG announced that it would invest 400 million U.S. dollars in establishing two "LG Beijing Towers" as China’s office center, and this was only one of the company’s four investment projects in China in the first half of 2002.

In the meantime, China’s FDI inflow in the form of merger and acquisition will also see a faster growth. This is because the governments at all levels have long had a strong desire to sell government-owned companies or government stocks. In addition, the new guidelines concerning the reform of government assets management system put forward at the 16th National Congress of the CPC will no doubt help the governments to release their stock rights and help promote mergers and acquisitions by foreign investors.

I. Moving from "unified ownership and indistinction between government administration and assets management" to "graded ownership and separation of government administration from assets management"

For long, our government-owned companies have failed to solve two basic issues: the unclear property right ownership and the indistinction between government administration and assets management.

First, are China’s several hundreds of thousands of government-owned companies all owned by the central government and managed by the governments at various levels, or are they owned by the governments at various levels? All the stipulations in the past emphasized that the state-owned assets were owned in a unified way by the State Council in the name of the state and were managed in a graded manner by the central and local governments. In other words, the central government was the owner, while the local governments were the managers. For this reason, the central government may hand over any poor-performing enterprises at any time to the local governments for "graded management", and may take over any well-performing enterprises from the local governments to "exercise ownership right". The earnings arising from the selling of stock rights by the local governments are sometimes placed under the control of the local governments (for example the non-listed companies), or sometimes placed under the control of the central government (for example the listed companies). With regard to the bad accounts incurred to the financial institutions of the local governments, the central government sometimes solves them on their behalf, and sometimes declares that "he who has the child takes care of him" (for example the case of the Guangdong International Trust Investment Corporation). It fails to say who owns the child. These are all signs of unclear property right ownership. If a foreign investor has reached an agreement with a local government on the terms of an enterprise’s merger and acquisition and then all of a sudden the government at the higher level says that the local government has no right to sell the enterprise, this will undoubtedly be something really annoying.

...

If you need the full context, please leave a message on the website.